|

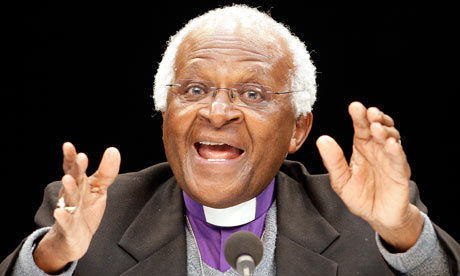

| Archbishop Desmond Tutu's leadership fellowship programme is helping entrepreneurs solve social problems across Africa. Photograph: Martin Meissner/Associated Press |

When 'Gbenga Sesan touched down onto the tarmac at Lagos airport, he folded up his ticket and tucked it into his jacket pocket. Hailing a cab straight to his office, he went to work right away. He was implementing what he had plotted out during the six-hour flight, and his airline ticket, covered in pencilled scribbles, was the blueprint for a new Lagos.

Sesan had just returned from Johannesburg, where he was one of 22 emerging leaders selected for the Archbishop Tutu leadership fellowship programme. Young Africans from business, government or development backgrounds had been selected in the early part of 2007, by the Africa Leadership Institute, and flown to a secluded conference centre in South Africa. There they were put through an intense series of seminars, discussions, lectures and exercises about leadership.

Critically, their course placed a huge emphasis on social entrepreneurship and ethical business. When the first participants had graduated in 2003, inspired by the curriculum and disgusted by widespread corruption, they spontaneously convened and wrote their own no-corruption pact, promising each other that they would avoid bribes, and use business as a force for social change. This tradition still continues at the end of each course, with participants signatures holding them to a code of conduct they hope will permeate the African continent as they grow older and ascend into power.

Africa could fit the landmasses of India, China, the US, Europe and Japan within its borders. So discussing its future is an ambitious task. It has taken the inspirational force of Tutu, and other leaders like Nelson Mandela, to force these discussions to start. Tutu embodies a classic model of African leadership – collaborative, serving the community, true to ones principles.

It's not the story that western newspapers always like to share, with African dictators like Robert Mugabe and Muammar Gadaffi more often grabbing the headlines. But the southern African philosophy of "ubuntu" is core to Tutu's teachings and is taught to all of his Tutu fellows. It is hard to strictly define, but Tutu, speaking in 2008, described it as "interconnectedness":

"You can't be human all by yourself, and when you have this quality – ubuntu – you are known for your generosity. We think of ourselves far too frequently as just individuals, separated from one another, whereas you are connected and what you do affects the whole world. When you do well, it spreads out; it is for the whole of humanity."

It was these words that had inspired Sesan when he stepped on to the plane home. His energy continued throughout the flight, stayed with him as he launched his training programme and still sustains him as he helps his fellow Nigerians get into work.

Unemployment is a major issue in Nigeria, with 90% of graduates unable to find full-time jobs. Many of these unemployed graduates come from disadvantaged communities, and find themselves sucked into an underworld of cybercrime and petty theft.

Sesan's employment and training programme, called Ajegungle.org, targets these unemployed but high-skilled individuals. Working in one of the poorest slums of Lagos, he improves their IT, entrepreneurial and communication skills, and then connects them with internships and local employers, or helps them start and grow their own small businesses. Since he attended the leadership programme in 2007, his work has positively touched over 13,000 young Nigerians.

Shane Immelman is another one of the seventeen inducted Tutu Fellows (class of 2008), an infectiously enthusiastic South African who builds and distributes lightweight and portable desks for African school children. Spurred on by a personal product endorsement from the Tutu himself, over 1.3m "Tutudesks" have now been distributed by his non-profit organisation.

There are an estimated 95 million African children without a classroom desk and Immelman aims to distribute at least 20m Tutudesks by the end of 2015, working around the clock to secure sponsorship deals, manufacture and distribute his portable writing surface. Without these desks, millions of African school children can't learn properly – critically impacting on their literacy, learning and academic development and performance. Independent field research shows that Tutudesks are improving handwriting, lengthening concentration spans and greatly improving teacher-pupil interactions.

Immelman is a proud white African, who chose social entrepreneurship as a way to redress some of the inequalities he sees across the continent. "Ethical leaders, in business as well as in public service, are the future," he argues. "There will always be people who want to let blood in the boardroom or use their position in government for personal gain. To some extent I understand those guys and their way of doing things, but the next generation of leaders will be more ethical and more conscious of the consequences of their actions. Chief executives are going to be appointed, who are saying – 'you can appoint me, but I'm going to do it my way'."

Tracey Webster, who graduated the programme in 2007, now runs the Branson's Centre for Entrepreneurship in South Africa, but previously founded a charity to care for orphaned and vulnerable children affected by HIV/Aids. Leaving behind her five-year banking career in London, she flew to South Africa and threw herself into creating a foundation that would care for forgotten children. By the time she left, 22,000 children were being fed, clothed and educated. Although her achievements are magnificent, the challenges still faced by South Africa are huge. There are more South Africans on state benefits than in employment and 79% of taxpayers are below the tax threshold and pay zero tax. Creating jobs has therefore become a high priority for government. But the administration doesn't offer help to social enterprises with tax breaks, credit or training.

"I found the lessons learned from the fellowship programme invaluable, especially about influencing and negotiating," explains Webster, who is determined to get more South Africans into jobs through the creation of micro and small enterprises. She is working with the government to try and make it easier for young South Africans to start their own businesses. As a hangover from apartheid, many black citizens do not have collateral, such as houses, cars, etc and most entrepreneurs are on pay-as-you-go mobile communication, hence don't have a credit history. Without this credit history, they cannot borrow to grow and expand their businesses, which is a contributing factor to the early stage business failure rate in South Africa

"Addressing challenges like this, understanding what needs to change for our dreams to come true, and then influencing the right people and working in partnership to get the job done, is what leadership is all about."

It's also about perseverance and staying power – the problems that Africa faces aren't going to respond to quick fixes. "We've heard some criticism about Toms Shoes. Although it's great that Africans are getting lots of free shoes, actually what you're doing is putting the little man in the street, who already makes and sells shoes, out of business."

It's a theme that runs across many of the conversations with Tutu's social entrepreneurs. What is the role of the west in defining Africa's future? Dambisa Moyo, a native of Zambia, Oxford-educated economist and Goldman Sachs veteran created a stir in 2009 with her book Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa, which argued that foreign aid to Africa has hurt, not helped the continent.

She argued that aid was an "unmitigated economic, political and humanitarian disaster" that has only made Africans poorer. It's a strong view, not without its detractors, but the social entrepreneurs enrolled by Tutu seem to agree that ethical business and up-skilling of Africans offers a better chance of success than relying on a stream of international donations.

That said, when Peter Wilson and Sean Lance set up the Africa Leadership Institute in 2003, they used their previous careers in pharmaceuticals, consultancy and bio-tech to set up lucrative sponsorship deals with western companies. The Tutu fellows are backed by funding from Investec, RioTinto and GlaxoSmithKline, as well as two African companies run by Tutu fellows, but funding is now a constraint on the further development of this successful programme.

However, their curriculum is defined by an African agenda, overseen by Tutu and welcomes only fellows of African origin. This is about finding internal solutions and weaning Africa off aid and philanthropy. And social enterprise is at its very core, and already bearing considerable fruit.

No comments:

Post a Comment